If you come across a portrait or photograph of the famous archaeologist, author and politician Austen Henry Layard, it is most often of him as an old gentleman with an enormous white beard. That beard is so big and white that he seems to be all beard and no person. But long before that he was a young man working in an office and longing for something—anything—more exciting.

Henry Austen Layard (he changed his name to Austen Henry to please the uncle who was supporting the family) was born in Paris in 1817. His father, a respectable Englishman, suffered from asthma, and living on the Continent was better for his health. It was also cheaper.

Young Layard’s eduation during their travels was a bit sketchy, introducing him to art and the joys of travel, but he enjoyed the somewhat Bohemian existence—more than he enjoyed public school, when the family eventually returned to  England.

England.

Once he was out of school, he had to earn a living, and spent several years in his uncle’s law firm, studying to be an attorney. He was grateful, but bored. When he was 22, he was offered a different opportunity by another uncle who had recently returned from Ceylon. He could go to be a lawyer there. That sounded a lot more exciting to Layard than working in a dreary London office.

Another young man, Edward Mitford, was going to Ceylon to start a coffee plantation, and they decided to travel together. The sea route was safer, but they thought traveling overland through Persia would be more exciting, and would allow them to visit the Holy Land. Being practical young men, they secured an advance from a publisher for a book about their travels.

It was indeed an adventurous journey, more so for Layard than for Mitford. There were times when Mitford decided, with some justification, that certain side trips were more dangerous than a sensible man would risk, but Layard went anyway. (The portrait at the right depicts the adventurous young Layard.) That was how he went to Petra—first hiring a local sheik to escort him. Such an arrangement sounded sensible, since anyone attacking him would bring on a feud with the sheik’s family. However, people were not always sensible. Robbers attacked anyway, and were driven off only because instead of surrendering, as a “sensible” man would, Layard charged at the robbers and put a pistol to the leader’s head. They decided he was more trouble than he was worth. Nonetheless, by the time he finally returned from this expedition, Layard was barefoot and penniless—and decidedly uncomfortable.

The most significant aspect of the journey, as far as Layard was concerned, came later. This was an encounter with Emile Botta, the French consul, who was excavating for antiquities in what he believed to be the ancient cities of Assyria. Layard thought that digging in the sand sounded like much more fun than being a clerk in Ceylon, and stopped his journey there. Mitford had to continue on his own.

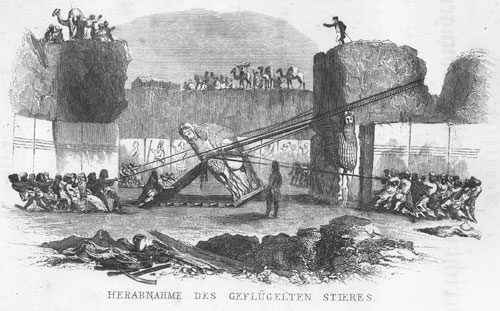

Layard persuaded the British ambassador in Constantinople to provide some funding and began his excavations in what proved to be the Assyrian city of Nimrud. His success was astounding. Among other things, he uncovered the huge stone heads and lion figures that guarded the gates of the ancient city. (The picture at the left shows just how strenuous an effort was involved in moving those works.) His discoveries over the next few years form the basis for what is today the Assyrian collection at the British Museum, and his assistant, Hormuzd Rassam (another fascinating figure), uncovered further wonders at Nineveh—the lion hunt bas reliefs and the clay tablets containing the Gilgamesh epic.

Layard persuaded the British ambassador in Constantinople to provide some funding and began his excavations in what proved to be the Assyrian city of Nimrud. His success was astounding. Among other things, he uncovered the huge stone heads and lion figures that guarded the gates of the ancient city. (The picture at the left shows just how strenuous an effort was involved in moving those works.) His discoveries over the next few years form the basis for what is today the Assyrian collection at the British Museum, and his assistant, Hormuzd Rassam (another fascinating figure), uncovered further wonders at Nineveh—the lion hunt bas reliefs and the clay tablets containing the Gilgamesh epic.

Layard’s excavations came to an end in the early 1850s, and the rest of his career was in govenrment and politics. However, his books about his adventures were best sellers in England, and even aside from their archaeological signifigance, they remain among the best travel books ever written. (They were the inspiration for Lady Emily's Exotic Journey, the next book in my Victorian Adventure series, coming on August 5.)

As a minor aside, interest in Assyria declined not long afterwards. The French, who continued working there, suffered a variety of discouraging disasters. That part of the world was perhaps not quite as dangerous then as it is today, but dangerous it was. The next major work there was undertaken in the 1920s by Max Mallowan. He was an important archaeologist, but his fame pales beside that of his wife—Agatha Christie.

Comments

hai

hai

Accidentally I have come

Accidentally I have come across this website and little bit confused about the details diamond rings shared here. You will get updates regarding more blogs over here that mainly belongs to the tales of romance and adventure. Happy to hear about this blog titled The Accidental Archaeologist. I am looking here to more updates regarding that.

hai

Accidental archaeologists are people who stumble upon ancient artifacts and sites without meaning to. Often, these artifacts and sites are found during construction projects or other forms of development. Accidental archaeologists help to uncover the history of an area, and can provide valuable information about the past. In some cases, diamond rings they may even help to preserve historical sites.

When you look at a portrait

When you look at a portrait of Austen Henry Layard, you may just see a man with an enormous white beard. But before he was a famous archaeologist, author and politician, he was once a young man real estate Molino stuck in an office job, yearning for something more. The Accidental Archaeologist is a reminder that anything is possible with hard work and a bit of luck.

Post new comment